Court considers striking murder conviction, death sentence of dead inmate

Gary Grado//October 7, 2013//[read_meter]

Court considers striking murder conviction, death sentence of dead inmate

Gary Grado//October 7, 2013//[read_meter]

The Arizona Supreme Court is weighing whether to wipe clean the murder conviction and death sentence of a dead man and how the rights of his victims will fit into its decision.

The Arizona Supreme Court is weighing whether to wipe clean the murder conviction and death sentence of a dead man and how the rights of his victims will fit into its decision.

The court heard arguments Oct. 1 on whether to overturn a trial judge’s decision to clear Richard Glassel of his convictions and death sentence for two counts of first-degree murder. He had also been sentenced to 351 years behind bars for 30 counts of attempted murder.

Glassel, who was possibly brain-damaged and definitely seething with rage, walked into the Ventana Lakes Homeowners Association meeting on April 19, 2000, carrying an AR-15 semi-automatic rifle and a .22 caliber handgun and opened fire on the crowd.

Glassel, 75, died of natural causes on Jan. 15. Judge Joseph Welty of Maricopa County Superior Court dismissed the indictment against Glassel, effectively leaving him as if he had never been charged. The judge did so because Glassel died before his appeal was resolved.

The Maricopa County Attorney’s Office asked the Supreme Court to nullify Welty’s decision and keep the criminal record intact. Some of Glassel’s victims asked the court to abolish the legal precedent on which Welty based his decision.

Welty relied on a 1979 Arizona Supreme Court case, State v. Griffin, which tackled abatement ab initio, a legal doctrine used when a criminal defendant dies before completing the appeals process.

The Supreme Court explained in 1979 that a defendant’s death makes it impossible to enforce a judgment. Abatement is used throughout the land, but some states have done away with it, limited it or modified it. One of the more notable cases in which the abatement doctrine was used involved former Enron executive Kenneth Lay, who died in 2006 before his sentencing on fraud and conspiracy convictions related to the collapse of the energy giant. The abatement meant his victims could not collect restitution.

“The rationale for death abating the criminal conviction is based on the fact that the interests of the state in protection of society have been satisfied, the imposition of punishment is impossible, and collection of fines or forfeiture result in punishing innocent third parties,” Justice William Holohan wrote for the 1979 Arizona Supreme Court in Griffin.

The victims

Duane Lynn and Esther LaPlante were board members sitting at a table in a packed HOA meeting, and Lynn’s wife of nearly 50 years, Nila, was in the audience.

Glassel, who had a series of disputes with the HOA, fired eight rounds from his .22 pistol, paused briefly, and fired two more times. Some men in the audience subdued Glassel as he reached for his rifle, but Nila Lynn lay dead with a bullet in her back. LaPlante was slain, too.

Attorney Colleen Clase of Arizona Voice for Crime Victims, who represents Duane Lynn and his adult children, said the abatement doctrine is outdated and inconsistent with victims’ rights.

She said the state had the interest of protecting society and doling out punishment when Griffin was decided, but now has the extra interest of upholding victims’ rights.

“The practice of abatement offends any notion of justice or fairness that a victim might have,” Clase said.

Arizona voters in 1990 passed the Victim Bill of Rights, the first of which is to “be treated with fairness, respect, and dignity.”

Clase pointed out that in recent years other states have either scaled back or abolished the abatement doctrine with respect to criminal cases.

Alaska recognized victims’ rights as part of the criminal justice system in abolishing the doctrine there, Clase said.

“We expect this trend to continue as the courts and public begin to appreciate the callous impact such a procedure may have on victims of violent crimes,” Clase said in a written brief.

Pretending it never happened

Gerald Grant, a deputy Maricopa County Attorney, told justices he would be happy if they abolished the abatement doctrine, but he wasn’t asking for that.

Grant argued that Griffin applied only to direct appeals, not post conviction relief proceedings, which is where Glassel’s case was when he died.

Grant’s argument was that Glassel’s conviction and sentence had already been upheld on appeal, and post-conviction relief proceedings are not considered a part of the constitutionally guaranteed appeal process.

Post-conviction relief proceedings are limited to issues that were not part of the record at trial such as newly discovered evidence or allegations the attorney at trial was ineffective.

“By applying abatement to the post conviction relief proceeding, which is where Mr. Glassel died before any of his claims could be resolved, essentially gives him the benefit of having earned something that he didn’t,” Grant said in court. “It gives him the benefit of having his convictions overturned.”

He said that erasing Glassel’s convictions would be like pretending they never happened, which would be an “egregious result for 32 victims and the community.”

Vice Chief Justice Scott Bales wanted to know what the state’s interest is in preserving the conviction of someone who died while his case was in post conviction proceedings instead of on appeal.

Grant said victims have a constitutional right to finality, and the abatement doctrine is not based in the Constitution or in statute.

“It is entirely judicially created and this court can set it aside,” Grant said.

Bizarre behavior

Defense attorney Charles Babbitt wrote that by all accounts Glassel was a normal man before a traffic accident in 1995.

His family reported that he began having problems reasoning, solving problems, his memory diminished and he began having problems coping with the difficulties of life, Babbitt wrote.

And he began acting bizarre, causing his wife to leave him.

He came to believe that gas fumes from cars parked in front of mailboxes were coming into his home, so he parked his car in front of them to keep others from parking there. The HOA towed his car away.

He also refused to let landscapers trim his bushes and trees and became belligerent when a representative of the HOA approached him about it. The HOA eventually sued him over the dispute.

Those disputes led him to picket in front of a Realtor’s office, and he ended up yelling at someone who tried to talk to him about the picketing. His house was foreclosed upon and he moved to California, but he returned a year later to seek his revenge.

Babbitt told the justices there was no doubt about Glassel’s guilt, but he was never given a fair trial because his attorney at trial never brought up any evidence to show he was seriously mentally ill when he committed the crime.

Glassel was alleging in post-conviction relief proceedings that his trial attorney was ineffective in not raising a defense of guilty except insane, which if the jury had found would have meant life in a mental institution instead of a death sentence.

Justice Robert Brutinel wanted to know why it matters that his record be wiped clean.

“It matters for him and his family because there is a substantial stigma associated with this conviction,” Babbitt said.

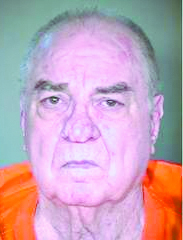

Richard Glassel

Crime: Convicted of shooting Esther LaPlante and Nila Lynn to death, wounding Edward Ettinger, Charles Yankowski and Gilbert McCurdy and threatening the lives of others at a Ventana Lakes Property Owners Association Meeting in Peoria, April 19, 2000.

Time on death row: 9 years.

Death: January 2013 of natural causes at age 75.

By the numbers

• 302 defendants sentenced to death in Arizona from 1973 to 2011

• 118 (39 percent) of those cases were reversed on appeal for one reason or another.

— SOURCE: Chief Justice Rebecca White Berch, Arizona Supreme Court.