Key Points:

-

Homeland Security Secretary claims right to build 40 miles of new border walls in Arizona

-

1996 law authorizes construction of physical barriers and roads along the border

-

Construction of wall along selected corridor could imperil jaguar existence in US

The nation’s top homeland official says she has the right to build new walls along nearly 40 miles of the border in southern Arizona, regardless of claims by environmental groups it could lead to the elimination of the jaguar from the state.

In new filings in federal court, a lawyer for Kristi Noem says the 1996 Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act specifically authorizes the Department of Homeland Security to construct physical barriers and roads along the border. More to the point, Alexander Yun says that law authorizes the secretary to “waive any legal requirements to ensure expeditious construction of border barriers and roads.”

And Yun brushes aside claims by the Arizona Center for Biological Diversity and CATalyst that Congress acted illegally when it amended the law in 2005 to say the head of the agency can “waive all legal requirements (that) such secretary, in the secretary’s sole discretion, determines necessary to ensure expeditious construction of the barriers and roads.”

“Such theories have no credible basis in constitutional jurisprudence,” he told U.S. District Court Judge Angela Martinez. “And every court to hear such challenges has unambiguously upheld the constitutionality of the statute.”

But Jean Su, attorney for the two groups that sued, said that while there may be a basis for the original law, the current version amounts to “unbridled — and unconstitutional — delegation of legislative authority.”

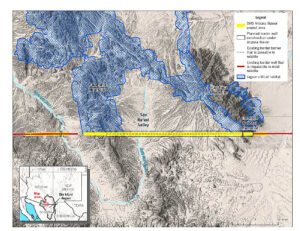

Hanging in the balance are two stretches of border where Noem has waived all laws.

One is a five-mile stretch from Nogales east. The longer one, more than 33 miles, runs from the Patagonia Mountains to the Coronado National Memorial.

The plans include 27 miles of new bollard walls — 30-foot-high barriers spaced four inches apart — to replace existing vehicle barriers which the challengers say are generally permeable and do not block wildlife movement.

“The San Rafael Valley is a critical lifeline, connecting imperiled jaguars and ocelots to vital breeding populations in Sonora,” the lawsuit says. It also calls it a “crucial corridor” for other specials like black bears, pronghorn, mountain lions, white tailed deer, mule deer, javelinas, coyotes and bobcats “who rely on transboundary movement between to search for shelter, food, mates, and other vital resources.”

“The Arizona Border Wall Project would essentially be the death knell for jaguars in the United States, eliminating over 53 years-worth of jaguar conservation efforts,” Su told the court. She also said that it would wipe out agency, organizational and tribal efforts, “leaving an irreplaceable void in the landscape that would be continuously felt by the communities who have lived beside them.”

Then there are factors ranging from the erection of stadium lights to the use of water for concrete and dust suppression.

“Finally, wall construction is planned to traverse the Santa Cruz River twice, which requires installing concrete foundations that disturb water flows of this already imperiled river,” Su wrote.

She wants Martinez to declare that Congress acted illegally in giving Noem total discretion to build what she wants without guidance or limits on what laws the secretary gets to waive.

Yun, in his newly filed response, makes no reference to the future of the jaguars if the wall is erected. In fact, his 24-page response to the lawsuit makes no mention of jaguars — or any other animal — at all.

Instead, Yun told the judge the case revolves around the law.

He said the original 1996 law specifically required the Homeland Security secretary to construct reinforced fencing along “not less than 700 miles of the southwest border where fencing would be most practical and effective.”

“Congress also gave the secretary the freedom to determine whether the placement of security items was ‘the most appropriate means to achieve and maintain control over the international border,”’ Yun said.

He acknowledged that the original statute limited the secretary to being able to override two specific laws: the Endangered Species Act and the National Environmental Policy Act. But Yun said that has since been expanded to “include all legal requirements.”

Yun also said that Congress clearly wanted to expedite matters, creating a “streamlined system of judicial review” for any lawsuits challenging the secretary’s authority.

First, it gave the federal court “exclusive jurisdiction” over these challenges. Potentially more significant, it limited those challenges to allegations of a constitutional violation.

He also said legal challenges must be brought within 60 days, and that the only way for someone unhappy with a trial judge’s decision to seek review is to take the case to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Yun said Noem did not pick the San Rafael Valley at random for the new barriers.

“The secretary chose these sections because she determined that the Tucson Sector is an area of high illegal entry, with over 463,000 illegal aliens and thousands of pounds of illegal drugs apprehended in 2024,” he told the judge.

Beyond that, Yun told Martinez there’s no basis for the claim by the environmental groups that Congress, in giving Noem that authority, had abdicated its role of prioritizing between competing values when it comes to border security. In fact, he argued, Congress did its job and told the secretary exactly what is the priority.

“By placing no limitations on the kinds of laws that may be waived, Congress prioritized border security over any other values, such as environmental concerns,” Yun said. “This prioritization is a clear mandate from Congress: construct barriers and roads at the border, and if another law impeded expeditious construction, the secretary may waive it.”

Anyway, he said, Congress did set “meaningful boundaries” on the authority given to Noem.

The first, said Yun, is geographic, with her ability to waive various other laws only in connection with construction “in the vicinity of the United States border.”

Second, he said, is that Noem can issue waivers only when “necessary to ensure expeditious construction” at those locations.

“The ample guidance provided in the IIRIRA (1996 law) is more than sufficient to constitute an intelligible principle and survive constitutional scrutiny,” Yum said.

No date has been set for a hearing.