Mayes sues Saudi farm over groundwater usage

Howard Fischer, Capitol Media Services//December 11, 2024//

Mayes sues Saudi farm over groundwater usage

Howard Fischer, Capitol Media Services//December 11, 2024//

Attorney General Kris Mayes is going to court with a largely untested legal theory in a bid to force a Saudi company to stop it from “excessively pumping groundwater” at its western Arizona alfalfa operations and require it to set aside funds to compensate neighbors it has damaged.

The lawsuit, filed Dec. 11, claims that Fondomonte LLC, the Arizona subsidiary of the company, has created a “public nuisance” by pumping so much water it has dried up nearby wells and already resulted in subsidence of the land around Vicksburg in La Paz County. But it also says that’s just the beginning, with the damage threatening sediment buildup that reduces water quality and damages appliances, pumps and pipes.

The only thing is, Mayes acknowledged, is that none of that pumping actually violates state water laws.

There are portions of the state that are within “active management areas” where pumping of groundwater is regulated. Pretty much everywhere else, including where Fondomonte operates, is ungoverned, meaning that those on the property have the right to grow what they want and, more to the point, pump as much water as they need for those crops.

Discussions at the Capitol about imposing new rules on these areas have broken down amid disputes over what regulations are appropriate. And Mayes blames the problem here on “legislative failure to address a water crisis with catastrophic effects on the groundwater level in the Ranegras Basin.”

That, she said, was the reason Fondomonte came here to grow alfalfa to feed dairy cattle in Saudi Arabia, where such farming is banned.

“Fondomonte is taking advantage of Arizona’s failure to protect its precious groundwater resources,” Mayes said.

And now the attorney general wants Maricopa County Superior Court Scott Minder to rule that, statutory limits on pumping or not, what Fondomonte is doing still violates the “public nuisance” provision of the state criminal code.

Fondomonte already is gearing up to fight the use of the nuisance law to curb what it says are its otherwise-legal operations.

“We believe the attorney general is setting a dangerous precedent attempting to penalize farming and the wider agricultural industry within the state of Arizona,” said spokesman Barrett Marson. “The company complies with all state and local regulations.”

But Mayes isn’t disputing that. Instead, the claim is that Fondomonte’s operations are harming its neighbors and, under Arizona law, creating a nuisance.

“Arizona law is clear on this point: No company has the right to endanger an entire community’s health and safety for its own gain,” Mayes said. “The law is clear on that point.”

Marson, however, said the allegations are “totally unfounded” and said the company will fight the litigation.

Arizona’s nuisance law has two methods of enforcement.

One makes it a Class 2 felony to maintain a public nuisance. But with the defendant being a limited liability company, jail time is off the table. That leaves only a fine of $750 that would make no difference in a case like this.

The other, though, allows her office to ask a court to enjoin the activity. That is precisely the order she wants here and a requirement for Fondomonte to set up an “abatement fund” to reimburse others who have been affected.

It will be up to a judge to decide whether the nuisance law fits what is happening here.

There really is no precedent.

The only known use of the law in a situation like this came earlier in Mayes’ tenure where she cited it to go after a company’s plan to start mining rock and gravel on a 25-acre parcel it owned in a neighborhood in a rural area near Chino Valley. The site was within 100 feet of homes.

State Mine Inspector Paul Marsh said at the time he had no choice under existing law but to approve the mining plan. So Mayes, claiming nuisance, got a court to issue a preliminary injunction.

But there never was a final ruling on whether the mine was a nuisance or whether the nuisance law applies: The lawsuit went away after the company abandoned its plan after someone else bought it.

In this case, Mayes said there is clear evidence of the effects of Fondomonte’s operations.

Operating in the Ranegras Basin since 2014, she said the company has multiple wells, each capable of pumping up to 4,000 gallons of water per minute. She said in 2023 alone, Fondomonte used about 31,196 acre-feet of groundwater within the basin. That is considered enough to serve about 93,000 single-family homes.

But the attorney general said there are more immediate and visible consequences.

Mayes said a well less than a mile from Fondomonte’s properties went dry about five years ago. And in late 2017, the same happened to a well for the Friendship Baptist Church about 1.8 miles away.

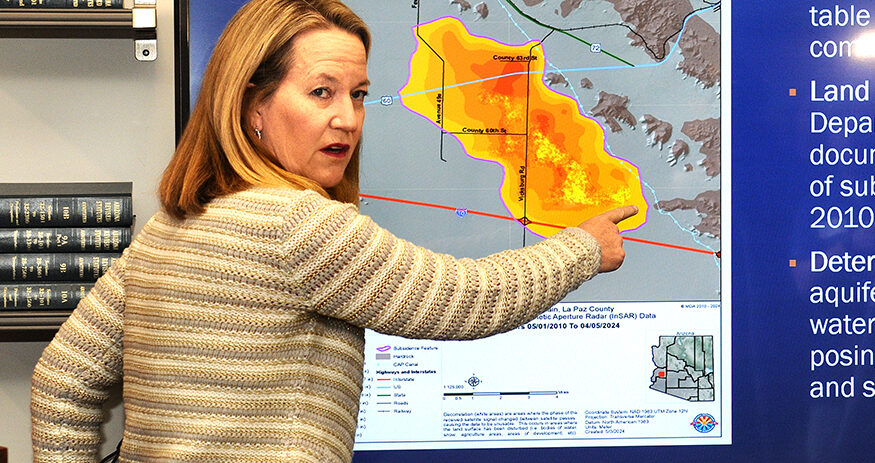

“The land is literally sinking in La Paz County with as much as 9.8 inches of subsidence documented in the immediate vicinity of Fondomonte’s farms,” she said.

All this, said Mayes, is enough to fit within the legal definition of a “public nuisance,” even if the company is not violating any other laws.

If this lawsuit succeeds, it won’t be the last. Mayes said Fondomonte is “not alone” in what she believes are actions by other large corporate farms operating in areas without pumping restrictions. And she already has her next target in mind.

“Cochise County is being seriously damaged by the Riverview Dairy,” she said, referring to the farm operating in the Willcox Basin. “The evidence of damage is just as strong, if not potentially stronger, than here.”

Still, Mayes said she is not arguing that the growing of alfalfa itself is a nuisance, acknowledging it is grown throughout the state by others, and that much of it is shipped overseas, including to China. She said the future of growing the water-intensive crop here “is a question for the Legislature.”

Mayes said, however, there is no excuse for lawmakers to have so far failed to take up the question of how to regulate water use outside the active management areas.

“They have been completely AWOL when it comes to addressing rural Arizona’s water needs and these situations where people are being harmed,” she said.

The attorney general isn’t the only one. La Paz County Supervisor Holly Irwin decried the lack of action by state lawmakers to place any restrictions on water use in her area.

“That is why we are seeing foreign companies come over to these areas, purchase land and pump water out so that they can supplement their alfalfa and send it back home,” said Irwin.

“Attorney General Kris Mayes is the first one who has stepped up and done anything about it,” said the Republican supervisor. “I know my constituents will be thrilled that somebody’s actually paying attention to the real problems here, which are wells that are going dry, the land subsidence that we’ve seen, and the concern that we have for the future of our basin.”

Efforts to address the problem have been stalled at the Capitol amid a dispute over not just whether regulation is needed but who should determine any restrictions.

Irwin and other rural supervisors want both monitoring and conservation of groundwater, pointing out that farms don’t even have to report how much they are pumping. But that has bumped up against agricultural interests who argue that, in many cases, they were here first and, even with the current targets being out-of-state and foreign firms, fear any potential state interference on their own operations.

So far, the agricultural interests have won out. In fact, lawmakers have carved out special protections.

For example, there is a state statute that says that agricultural operations that were around before surrounding residential development “are presumed to be reasonable and do not constitute a nuisance.”

Mayes, however, said that doesn’t apply, and not only because residents were there long before Fondomonte started farming alfalfa and pumping groundwater in 2014.

She also pointed out that same law does not apply if “the agricultural operation has a substantial adverse effect on public health and safety.” And Mayes, in her lawsuit, spoke to the exception, calling the excessive pumping “injurious to health” and even “indecent” because it interferes with the ability of people to enjoy their property.

Republican lawmakers, anticipating last year what Mayes was going to do, even tried to undermine her ability to sue. Sen. Sine Kerr, R-Buckeye, added a provision to HB 2124 dealing with agricultural water use to strip the attorney general of the right to bring any sort of nuisance action at all, regardless of the reason.

That bill was vetoed by Gov. Katie Hobbs.

But the governor, in her veto message, made no specific mention of that change. Instead she said lawmakers need to address water issues “in a holistic manner” rather than tinkering with water laws on a piece-meal basis.